“Don’t look back,” the baseball sage Satchel Paige advised. “Something might be gaining on you.” For Bob Dylan in the 1960s, the hellhounds in the rearview were the crush of celebrity and the weight of ridiculous expectations.

Martin Scorsese’s “No Direction Home: Bob Dylan” starts off in Ken Burns territory, using a rich and exquisite mix of vintage sounds and images to track Robert Zimmerman of Hibbing, Minn., as he moves to New York and becomes folk singer Bob Dylan.

The documentary ends a half-decade later, with a speed-jacked-hollow-eyed Dylan rocking back and forth on a couch repetitively, as if he’d been dusted with autism. “Traitor!” they had yelled at him one too many nights. “I just want to go home,” the shellshocked rock star moans.

The documentary ends a half-decade later, with a speed-jacked-hollow-eyed Dylan rocking back and forth on a couch repetitively, as if he’d been dusted with autism. “Traitor!” they had yelled at him one too many nights. “I just want to go home,” the shellshocked rock star moans.

Dylan’s long search for a place to be looms large in Scorsese’s compelling two-part film, released by Paramount Home Entertainment as a double-DVD set (released in fall 2005).

“I was born very far from where I’m supposed to be,” Dylan says today, as the 3 1/2-hour docu opens. “So maybe I’m on my way home.”

Dylan acts as his own witness throughout — at ease, clear, sometimes funny and seemingly pleased to take control of his legend, much as he was last year on “60 Minutes.”

Other key interviewees include musicians Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Maria Muldaur and Al Kooper, as well as one-time ladyfriend Suze Rotolo and the folk-music promoter Harold Leventhal. Dylan’s mentor Dave Van Ronk and the beat poet Allen Ginsberg were interviewed before their deaths.

The film’s subtitle should be something like “Bob Dylan, 1960-65.” The recorded output during the period stretches from the walkthrough debut album “Bob Dylan” (1962) to the titanic “Highway 61 Revisited” (1965).

“I don’t feel like I had a past,” Dylan says, but the assembled evidence proves otherwise. Part 1 unspools much like a video companion to Dylan’s vastly entertaining biography “Chronicles, Volume One,” which covers his years on the Greenwich Village folk scene, the epicenter of American hip in the early 1960s.

Dylan first came to New York on a quest to meet his idol Woody Guthrie, the iconic folksinger whose Huntington’s disease landed him in a mental hospital. Dylan says no one reached him musically before Guthrie. “It was the sound (of other singers) that got to me,” he recalls. “It wasn’t who it was.” Scorsese shows seldom-seen clips of performances by such artists of the day as Hank Williams, Gene Vincent, Odetta and Muddy Waters. (The 5.1 audio, irrespective of source material, is stunning throughout.)

Guthrie “had a particular sound, and besides that he said something,” Dylan recalls. “He was a radical — (I thought) that’s what I want to say. I want to say that.”

Dylan found a reason to believe in the craft of songwriting, and once he started, “I wrote ’em anywhere I was — in a subway, a cafe. … I wrote the songs to perform the songs … in a language I hadn’t heard before.”

A dubious Baez, the folkie madonna, came to see the phenom perform. “He was everything they said he was.” The singers became lovers and collaborators. “I knew he was going to be a massive star, and I liked that,” she says today, delightfully rough and ready in her maturity.

The folk movement’s old guard embraced Dylan, anointing him at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival. “Blowin’ in the Wind” became an all-purpose anthem for the socially aware. Dylan was branded a protest singer, a label he rejected, most of the time. Of “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” he told Studs Terkel’s radio audience: “It’s not an atomic rain. It’s just a hard rain.”

Ginsberg recalled discovering Dylan in the hottest days of the Cold War. “I heard ‘Hard Rain’ and wept. … It seemed the torch had been passed (from the Beats) to a new generation.” On the scariest night of the Cuban missile crisis, Dylan played the Gaslight coffeehouse and sang “Masters of War.”

Part 1 goes on to chronicle Dylan’s rise to international stardom after signing with Columbia. The documentary’s gentle rhythms turn propulsive as his early recordings annex the soundtrack. At first, industry wags dismissed Dylan as producer “John Hammond’s folly,” but most everyone got it, especially the college kids coming out of the 1950s looking for someone to follow.

“It’s almost enough to make you believe in Jung’s notion of collective unconscious,” Van Ronk said. “If there is an American collective unconscious, Bobby had somehow tapped into it.”

“No Direction Home” becomes A Film by Martin Scorsese in its dark concluding act. Like the director’s “Mean Streets” and “GoodFellas,” it captures the paranoia and disintegration as the central character’s life implodes.

“No Direction Home” becomes A Film by Martin Scorsese in its dark concluding act. Like the director’s “Mean Streets” and “GoodFellas,” it captures the paranoia and disintegration as the central character’s life implodes.

As Scorsese and his collaborators spin the tale, Dylan’s torments come solely as punishment for artistic metamorphosis — the treasonous act of going electric after finding fame as a dutiful folk singer. “No Direction Home” sidesteps Dylan’s chaotic personal life and drug use.

The artist faced a far-flung confederacy of dunces, Scorsese maintains: moronic reporters, abusive audiences, uncomprehending music lovers, petulant folkies, teenagers who shrieked, fawned and grabbed. No one seems to have any sense except for Dylan and his in-crowd.

Dylan’s songs play nonstop in that gorgeous audio, but there is little discussion, surprisingly, of the groundbreaking music he produced in the mid-’60s — no recognition of the vast baby boom audience that heard the genius in his explorations and embraced them. No one testifies to the deep and immediate influence of “Highway 61 Revisited” on rock innovators up to and including John Lennon.

Still, it’s easy and satisfying to buy into Scorsese’s view of Dylan as underdog. The slant and subjectivity give “No Direction Home” much of its drama and depth, especially in the final hour.

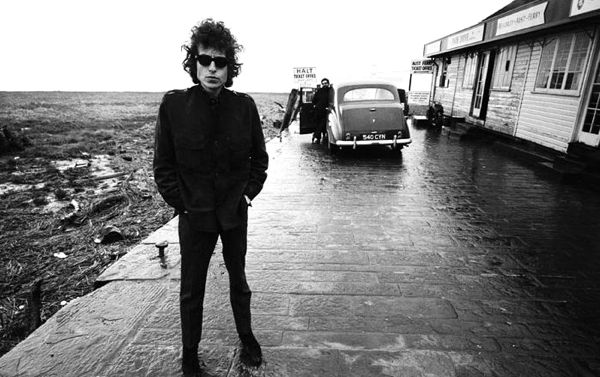

Part 2 leans on footage from the films “Don’t Look Back,” about Dylan’s 1965 tour of Britain, and “Festival,” which captured the shootout at Newport. Included are famous scenes such as the “Mr. Jones” confrontation with a British reporter and the seminal cue-card video for “Subterranean Homesick Blues.”

(Those films’ directors, D.A. Pennebaker and Murray Lerner, respectively, get third billing in “No Direction Home,” after Scorsese and his gifted editor, David Tedeschi. Still photographer Barry Feinstein and interviewer Jeff Rosen, Dylan’s manager, are other key contributors.)

In the remarkable footage from Newport ’65, Dylan jolts the folkies by enlisting Kooper and members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band for a quick set of rock songs. The boos and catcalls compete with the amplified din. Dylan’s freaked-out friend Seeger calls for an ax with which to cut the power cables, reports of which wound Dylan “like a dagger.”

“I had no idea why they were booing,” Dylan says today with a straight face. “Whatever it was about it wasn’t about anything they were hearing.” Accounts of that night don’t add up, but it was hardly an ambush by Dylan: The rock album “Bringing It All Back Home” had been out for four months.

Booing Dylan became sport and populist performance art when he next toured, finishing the show with rock musicians. Sometimes Dylan would sass them back, playfully. Sometimes he would snarl. Of the backup band that became the Band, he says, “They were gallant knights for standing behind me.”

Pennebaker and his cameras were back in England on May 17, 1966, when the group played Manchester. “Judas!” a British fan screams at Dylan as he takes the stage. “I don’t believe you,” the musician says in the legendary exchange. “You’re a liar.”

Dylan turns to his bandmates, commanding, “Play it fucking loud!” They roar through “Like a Rolling Stone” like scorched-earth warriors. For Scorsese and his audience, the ride ends here, with Dylan taking a hard right at the crossroads.

When you get to the end, you want to start all over again. That’s the No. 1 reason to invest in Paramount’s “No Direction Home: Bob Dylan” DVD.

Coming from a project so awash in audio and video treasures, it seems odd that the only meaningful DVD extras are complete versions of Dylan numbers trimmed for the documentary.

That said, there are some great performances here — for example, the eight-minute version of “Like a Rolling Stone” from the 1966 tour of Britain and the hypnotic “Mr. Tambourine Man” from a Newport workshop in 1964. (There are five others, some odd, all worthwhile.)

A quartet of guest performances from singers interviewed for the docu don’t add much, except for Baez’s home-cooked “Love Is Just a Four-Letter Word.”

There also is an interesting “unused” 1965 promo for “Positively Fourth Street” — unfinished is more like it — and a clip of Dylan crafting a song in a hotel.

The DVD’s Dolby Digital 5.1 audio achieves reference quality. The 2003 remastering jobs on Dylan’s early and midperiod recordings (for SACD hybrids) possibly came into play.

Images are TV-friendly full-screen, with pleasing grays and medium contrasts. The video texture is amazingly consistent given the Babylon of sources.

More music video reviews:

- “The Last Waltz”

- “A Hard Day’s Night” on Criterion

- “Marley”

- “X: The Unheard Music” and “Sid and Nancy”

Check out Glenn Abel on Google+

Leave a Reply