The long-awaited Blu-ray of “A Hard Day’s Night” comes with the prominent subtitle: Directed by Richard Lester.

Truth in packaging, as the Criterion Collection’s smashing release of the Beatles’ film puts the focus squarely on the iconoclastic director, whose vision and bravery under fire made what could have been a forgettable “jukebox musical” into a classic of several genres.

“A Hard Day’s Night” makes most critics’ best-ever lists. The Beatles’ first and best film is widely considered an electrifying mix of great music and hip comedy, both a time capsule of the swinging ’60s and a timeless entertainment. Roger Ebert called it “one of the great life-affirming landmarks of the movies.”

“A Hard Day’s Night” makes most critics’ best-ever lists. The Beatles’ first and best film is widely considered an electrifying mix of great music and hip comedy, both a time capsule of the swinging ’60s and a timeless entertainment. Roger Ebert called it “one of the great life-affirming landmarks of the movies.”

Respect hadn’t led to respectful treatment. Legal wrangling followed “A Hard Day’s Night” throughout its home video life, resulting in oddities like the “tribute to John Lennon” musical prologue tacked on for VHS. The first DVD version, from MPI in 1997, disappeared after a few months of distribution.

The black-and-white “A Hard Day’s Night” was one of the high-profile Criterion titles on laserdisc, but most DVD-era editions of the Beatles film came from Miramax/Universal. (A Blu-ray debuted in 2009 but proved problematic and quick went out of print.)

Here, finally, is a definitive version. The film unspools at a 1.75:1 ratio, as shot — letterboxed no doubt to not repeat some of the odd cropping inflicted on the title over the years. The restoration work is no less than stunning. The images look straight from one of Criterion’s ace presentations of Euro film classics.

Audio defaults to a bracing mono, but there are also 5.1 and stereo mixes undertaken by Gilles Martin (“Love”) and Sam Okell at Abbey Road Studios. (Their adventures are detailed in the set’s booklet.)

Criterion’s extras are somethings new and old.

Debuting special features are “In Their Own Voices,” 18 minutes of audio clips of the Beatles talking to the press about “A Hard Day’s Night”; a fine short film about Lester’s body of work, featuring a sharp new audio interview with the director; “Anatomy of a Style,” a watery piece about the film’s inexhaustible reservoir of hip; and an outstanding video interview with Mark Lewisohn, author of the massive new book(s) “Tune In: The Beatles: All These Years.”

Pop-culture critic Howard Hampton (“Born in Flames: Termite Dreams, Dialectical Fairy Tales, and Pop Apocalypses”) wrote the intro to the “Hard Day’s Night” set’s thick booklet. It also includes a dated but interesting film-magazine interview with Lester, and the usual detailed notes about the Criterion set’s restoration and audio work.

Pop-culture critic Howard Hampton (“Born in Flames: Termite Dreams, Dialectical Fairy Tales, and Pop Apocalypses”) wrote the intro to the “Hard Day’s Night” set’s thick booklet. It also includes a dated but interesting film-magazine interview with Lester, and the usual detailed notes about the Criterion set’s restoration and audio work.

Returning extra features include the obligatory Lester short “The Running Jumping and Standing Still Film”; the decent Phil Collins-hosted “You Can’t Do That: The Making of A Hard Day’s Night” from 1994; an audio commentary from 2002 featuring various members of the film’s cast and crew but none of the Beatles; a deleted scene; and a trailer.

(Completists with the 2002 Miramax DVD may want to hold on to their copies, as many of its interviews aren’t ported over. Some are used as reference in this review.)

Back in 1964, few expected much of the Beatles’ film, especially the Fab Four. Pop movies of the day usually were hit-and-run affairs, with singers inexplicably breaking into slapdash song while extras gyrated.

The Beatles “had the courage to reject probably a half dozen film offers,” says biographer Lewisohn. “They were running the risk of never appearing in one at all” if their fame ran out. Lewisohn, who talks mostly about the band’s early years, notes that the Beatles were hardly lads, but pros who were “halfway through their career path” together.

Already a sensation in Britain, the Beatles had the clout to influence the choice of director. They went with Lester, who worked with Peter Sellers and his pals on TV versions of their radio “The Goon Show.” The Fabs especially admired Lester’s “Running, Jumping, Standing Still Film,” the madcap short made for £70 and nominated for an Academy Award.

“They thought they could trust me to produce that same sort of useless amateurism that they’d noticed before,” Lester remembers. The American expatriate went on to helm the second Beatles’ film, “Help!” recently rereleased to Blu-ray.

UA turned control of the film over to Lester, producer Walter Shenson and Liverpool writer Alun Owen, effectively giving the trio final cut. The UA execs came to expect a “strange little movie” that would be made quickly, on a tight budget. Postproduction was allotted 3 1/2 weeks.

“In our price range, we didn’t even think of using color,” says Lester, who was greatly influenced by the dramatic blacks and whites of the French New Wavers such as Truffaut and Godard. (The Criterion treatment showcases “A Hard Day’s Night’s” sophisticated cinematography and editing.)

“A Hard Day’s Night” was shot with great secrecy because of the group’s skyrocketing celebrity. Lester shot the film in London after the Beatles’ first trip to the States, which featured their history-making “Ed Sullivan Show” debut. The movie’s concept was to follow a fictional pop group (technically not scripted as the Beatles) as they traveled by rail to an important TV gig. (Note that there’s a reference to Lennon’s mother, clearly fiction as she had been dead since 1958.)

The screaming fans seen chasing the lads throughout the streets of London were, in fact, screaming fans. The group “caused absolute mayhem wherever they went,” says Jeremy Lloyd, the pogoing dancer in the film’s club scene. “It was awful,” one actress recalls. On the first day of shooting, an assistant carrying exposed film panicked when surrounded by fans and lost a half-day’s shooting as he ran for his life.

Although it seems the Beatles ad-libbed their way through the movie, Lester says only about 5 percent of the dialogue wasn’t in Owen’s script. The Beatles came up with a few comic riffs, Lester says, but the musicians knew they were way out of their element and did what they were told. Still, as Lewisohn says, the Beatles were “naturally hilarious.”

Owen had an extraordinary grasp of the group’s offbeat humor, even if he did limit the non-actors to one-liners. Lester and Owen felt it was important to create distinct personalities for each member of the group. (Still, Groucho Marx crabbed that the boys couldn’t be told apart.) “The stereotypes still go on to this day,” the Beatles’ music producer George Martin says. “They were not true.”

Owen had an extraordinary grasp of the group’s offbeat humor, even if he did limit the non-actors to one-liners. Lester and Owen felt it was important to create distinct personalities for each member of the group. (Still, Groucho Marx crabbed that the boys couldn’t be told apart.) “The stereotypes still go on to this day,” the Beatles’ music producer George Martin says. “They were not true.”

Lester said he was trusting of “adrenaline and sheer momentum” during the filming.

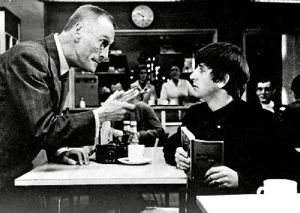

Brought in to provide acting chops was Wilfrid Brambell, who played the Redd Foxx part in the British show that inspired “Sanford and Son.” Although the boys mostly kept their distance from the all-business TV star, they became quick friends with other actors. Choreographer Lionel Blair says the Fabs “liked the older stars, people who had been on the box for a long time. They had respect for us.”

Interviewees repeatedly praise the Beatles for being easygoing “nonstars.” “I don’t know how they managed to stay sane and be the guys they were,” says David Janson, who played Ringo Starr’s young sidekick David Jaxon in the film.

Lester says George Harrison was “the most accurate” actor in the band. “He never attempted too much or too little.” Paul McCartney, who was dating actress Jane Asher, “tried too hard to act,” the director remembers. “He loved show business, while the others didn’t care.” (McCartney’s solo spot was cut from the film.) Starr “had a dubious expression permanently” and worked his big solo scene with a hangover. Lester greatly admired Lennon, who was quick with ad libs and “suffered fools very badly.”

The film’s thrilling final scene, a concert in a theater/TV studio, featured some of the production’s worst craziness and greatest creativity. The seats were filled with acting students (including a young Phil Collins), but the real fans wouldn’t be denied. Climbing in from the roof, they sawed locks off and rushed down. There were numerous accidents in the crush. Fans tore up seats, some becoming sick and others passing out. The crew had no way of communicating because of the screeching. (Incredibly, more screams sweetened the mix in postproduction.)

Six brave cameramen worked the mini-concert, making rock history amid the chaos. (One cameraman’s work was discarded, Lester says, because he simply didn’t grok what was going on.) True to Lester’s style, the lensmen were free to shoot as they liked, lingering on the instruments, shifting depth of field and shooting at unexpected angles. (“A Hard Day’s Night” actually gets that guitar playing was key to the Beatles’ power, and shows them fingering their fretboards.)

The TV auditorium scene never fails to amaze. “We established a style that’s still used today when they photograph pop stars,” cameraman Paul Wilson says. Editor John Jympson is repeatedly praised for pulling together a tightly paced film from a mountain of material.

Hit songs include “Tell Me Why,” “She Loves You,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “I Should Have Known Better” and “If I Fell.”

In addition to the dual-format Criterion release (Blu-ray and DVDs, about $25), there’s also a single-DVD edition.

More music video reviews:

Check out Glenn Abel on Google+

Leave a Reply