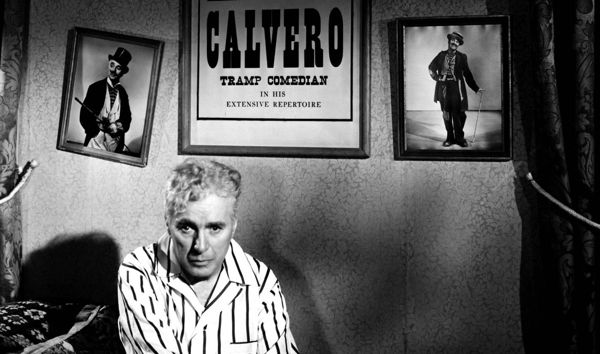

“The cycle is complete,” the not-so-great Calvaro says in Charles Chaplin’s “Limelight.”

It was more than a line from a self-pitying clown. Chaplin’s 1952 film completes the circuit between the pure joyous comedy of his youth and the time-weary art of his advanced years. Chaplin, fully expecting “Limelight” to be his last film, made it his last testament.

To this day, the audiences don’t know whether to laugh or cry when encountering the long-winded melodrama about an aged music-hall performer and a troubled young ballerina.

Director Bernardo Bertolucci is among those who consider “Limelight” Chaplin’s masterpiece.

When the “tramp clown” breathes his last, “Who is dying here is not Calvaro, but Charlie Chaplin,” Bertolucci says. “With ‘Limelight,’ tears flow very easily.”

When the “tramp clown” breathes his last, “Who is dying here is not Calvaro, but Charlie Chaplin,” Bertolucci says. “With ‘Limelight,’ tears flow very easily.”

The Criterion Collection adds to its sporadic Chaplin efforts with a splendid Blu-ray of a restored “Limelight,” bolstered by several new bonus features and the half-hour MK2 documentary that accompanied the film’s last major release, by Warner Home Video in 2003. Owners of that “Chaplin Collection” title should compare extras with the Criterion disc, which isn’t quite as extensive but perhaps more to the point.

Chaplin biographer David Robinson participated in both the Criterion and Warner projects. For Criterion, he created a new piece on the “Evolution and Intimacy” of “Limelight,” in which he tracks Chaplin’s concept back to 1917, when the superstar comic met and was gobsmacked by Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. Years later, Chaplin wrote a treatment about a Nijinsky-like dancer and his kindness toward another artist in decline, but instead made “The Great Dictator,” under the influence of world events.

The dance concept rattled around over the decades, until the early ’50s. Chaplin was by then far too old to play a dancer, so the story became one of an alcoholic comic who saves a ballerina from herself. Robinson notes that Chaplin was “morbidly fascinated” by reports of suicides of washed-up comedians.

The story originally came in novella form, dubbed “Footlights,” which Chaplin apparently never intended for publication. (He reads a smidgen of the manuscript in the supplemental features.)

Chaplin sought a co-star who was young, short (to match his stature) and able to pull off the illusion of being a ballet dancer. He found Claire Bloom, who had classical training in drama and had studied ballet. The British actress, still lovely and still working these days, recalls that her mother kept a good eye on Chaplin, infamous for his affairs with young women.

In the post-war years, Chaplin, who never became a U.S. citizen, was known as a “peacemonger.” He was chased by the hellhounds of the extreme right and probed by the feds. “He was being studied by the FBI; we all knew that,” Bloom says. Chaplin sought refuge from his political woes in the music-hall memories of his youth. He and art director Eugene Lourie re-created London of 1914 on a lot at Paramount. The story was populated by show-business people who lived and worked in Soho.

It was in some ways a family affair: Bloom recalls being costumed to resemble Chaplin’s mother and his childhood sweetheart. Calvaro the clown was loosely based on the comic’s father. (More than a half dozen Chaplin family members have parts in the film, including his son Sydney and daughter Geraldine.)

The story was partly a celebration of Chaplin’s real-life marriage to the much-younger Oona, who even appears for a second as a stand-in for Bloom. “Limelight” cast member Norman Lloyd, interviewed by Criterion in 2012, says Chaplin “sought to dramatize the pain and the difficulty and above all the love that went into (that May-September relationship).”

Still, Bloom says of her beautiful ballerina, “Many things that were part of my nature were part of her.” (Bloom also appears on the Criterion disc via a 2015 sit-down interview.) Lloyd agrees that Bloom was a “strong” actress even at her young age, able to deal with — and learn from — the “demanding” Chaplin.

The Blu-ray’s docus don’t address the old charges that Chaplin spiked Buster Keaton’s best work in the film. Regardless, the extended Keaton-Chaplin slapstick sequence late in the film remains the highlight for many viewers. Lloyd watched with wonder as the silent-film veterans improvised — “the top of professionalism.”

Criterion’s presentation of “Limelight” includes two shorts, notably the hilarious 1919 bit with Chaplin on the loose as a flea-circus wrangler. The other is “A Night in the Show” (1915). There’s also an outtake (the chat with no-arm man) and several trailers. A 42-page booklet features text by critic Peter Von Bagh and on-the-set columnist Henry Gris.

The handsome images unspool in the the original 1.37:1 with black framing left and right. The restoration was done by Criterion using the original 35mm negative. The restored (mono) audio comes from the 35mm sound negative.

- More Chaplin: “The Gold Rush” on Criterion.

Leave a Reply