A plain-speaking western hero makes a lonely stand against a gang of outlaws. The clock ticks down. The townsfolk cower. A train steam-bellows down the tracks, its arrival presaging a shootout and near-certain death for the hero.

A plain-speaking western hero makes a lonely stand against a gang of outlaws. The clock ticks down. The townsfolk cower. A train steam-bellows down the tracks, its arrival presaging a shootout and near-certain death for the hero.

That’s “High Noon” all right, one of the most famous American westerns. But it’s also “3:10 to Yuma,” a lesser-known film that came five years later.

“High Noon” seems to have suffered a critical downgrade over the past decade or so, perhaps due to its heavy-handed dramatics. Delmer Daves’ blacklist-era western “3:10 to Yuma” proves a far superior film about lone justice, its moral ambiguities better suited to modern audiences.

A year ago, “Yuma” entered the National Film Registry (joining “High Noon”). Now the Criterion Collection gives the film its due with splendid new Blu-ray and DVD editions that utilize a restoration and mastering by Sony (Grover Crisp at the helm).

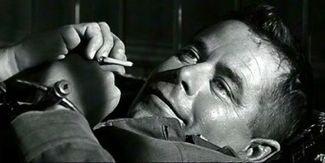

Glenn Ford plays a slick and seasoned outlaw accustomed to business-like robberies. He’d rather get his loot without drama or loss of life — the gang treats its victims civilly, unless they’re gunning them down. During a stagecoach robbery, he encounters a homesteader (Van Heflin) more concerned about his cattle than the outlaws’ crime in progress.

The gang leader is captured solo in a nearby town and must be transported across the drought-plagued landscape to Yuma, Ariz., where prison awaits. Desperate for money to keep his family and farm going, the homesteader takes the job. The hellhound gang follows, desperadoes waiting for a train.

There is a Hannibal Lecter inevitablity to the outlaw’s escape, a dynamic played out beautifully by Ford and Van Heflin, as the glib prisoner and the exhausted farmer wait in a hotel room. The movie is about that relationship and existential morality. (One good thing that came out of the blacklist era: some great existential movies.)

There is a Hannibal Lecter inevitablity to the outlaw’s escape, a dynamic played out beautifully by Ford and Van Heflin, as the glib prisoner and the exhausted farmer wait in a hotel room. The movie is about that relationship and existential morality. (One good thing that came out of the blacklist era: some great existential movies.)

“3:10 to Yuma” is one of those films where lines are conserved like desert water. TV western veteran Halsted Welles (working from a Elmore Leonard magazine story) makes every word earn its keep — the script is a marvel of dramatic precision.

The homesteader tells his wife how the $200 can change their dirt-level lives: “Maybe in six months, we won’t be as tired all the time.” What more needs to be said.

Charles “Buddy” Lawton Jr.’s bracing black-and-white images seem influenced by the Europeans such as Ingmar Bergman and the Italian neo-realists. At times they recall the war photography of Robert Capra. Far from the majesty found on the land by John Ford and George Stevens.

Lawton used red filters on b&w stock in pursuit of the hard contrasts sought by director Daves. The idea was to dramatize the drought that slips the plot into gear. “The result is a western that looks like no other,” says Kent Jones, who wrote the booklet essay for Criterion.

At times, the actors look unworldly, specters in a dreamscape drained of color. In some closeups, their eyes take on a spooky bible black. (The aspect ratio is 1.85:1, as shot, with black bars top and bottom.)

Was “Yuma” a knockoff of “High Noon”? Leonard, who wrote the original short story for Dime Western Magazine a year after “High Noon’s” release, says “perhaps it was in my mind, maybe it wasn’t.” In any case, he got paid, about $90, good money for the day. “I was happy.”

Leonard, who does a terrific 13-minute video interview in the Criterion extra features, says he’s a fan of the original movie and the casting of Ford, who was “absolutely perfect.” Ford was up for the Van Heflin role, but the actor convinced the filmmakers he’d be better as the villain.

As for the 2007 remake with Russell Crowe in the Ford role, Leonard found the ending — in which the gang leader guns down his own men so the farmer haul him off to prison — “doesn’t make sense.” Leonard says he later asked the screenwriters why they gave his tale such an improbable finale, and they pointed the finger at director James Mangold.

Leonard, wildly successful as a writer of crime novels (“Out of Sight,” “Get Shorty”), says he stopped writing westerns when the genre became a TV staple in the late 1950s. “I didn’t like any of them,” he says of “Gunsmoke” and the rest.

Ford’s son (and biographer) Peter Ford does a brief talk about his dad, noting that the Canadian actor “hated dialog.” Ford “loved Del” (the director) and “had his issues with method people.” The prolific ladies man also had a thing for “Yuma” co-star Felicia Farr, his son said. “He liked her a lot.”

Ford’s son (and biographer) Peter Ford does a brief talk about his dad, noting that the Canadian actor “hated dialog.” Ford “loved Del” (the director) and “had his issues with method people.” The prolific ladies man also had a thing for “Yuma” co-star Felicia Farr, his son said. “He liked her a lot.”

Farr had a more significant role in 1956’s “Jubal,” an oater take on “Othello” that was directed by Daves and also starred Ford. Criterion released this color title — as upgraded by Sony — in conjunction with “Yuma” in a fine looking edition that comes without extras. Ernest Borgnine is terrific as the good-hearted cuckold; Rod Steiger’s work just might turn you against the method gang as well.

The last “3:10 to Yuma” video release came in 2007, when Sony Pictures Home Entertainment smartly hitched a ride on the theatrical remake, putting out a newly remastered edition. Another revelatory job from that video shop in which the high hard contrasts popped off the screen.

Glenn Abel on Google+

Leave a Reply