In retrospect, “Trilogy of Life” seems an odd and ironic title for any work credited to Pier Paolo Pasolini.

In retrospect, “Trilogy of Life” seems an odd and ironic title for any work credited to Pier Paolo Pasolini.

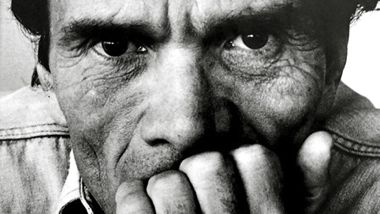

The director’s grisly murder in 1975 still haunts Italians. Pasolini’s notorious work “Salò” is a study in death and depravity — a sick work of art, but an essential work of art nonetheless. His was dubbed “the cinema of despair.”

In the U.S., Pasolini is most remembered for this darkness, when he is remembered at all.

“The idea that death defines a person has seldom been more vividly illustrated than in the case of Pasolini,” the New York Times wrote in its piece on the major Pasolini retrospective at the Museum of the Modern Art. The late 2012 series was the most complete Pasolini retrospective in New York (and probably the U.S.) in more than two decades.

The Criterion Collection also seeks to raise and redefine — or at least rehabilitate — Pasolini’s profile in North America with the release of “Trilogy of Life” to Blu-ray and DVD. The outstanding three-disc set includes the pre-modern literary adaptations Pasolini released from 1971 to 1974: “The Decameron,” “The Canterbury Tales” and “Arabian Nights.”

“I always see things as being a bit miraculous,” Pasolini says, perhaps in self-defense, in a filmed interview in the bonus features. He calls his films “the cinema of poetry.”

“I always see things as being a bit miraculous,” Pasolini says, perhaps in self-defense, in a filmed interview in the bonus features. He calls his films “the cinema of poetry.”

He refers to the “Trilogy of Life” as his “most political work.” It’s hard to see that way. The films examine humanity at gut levels: love, greed, raw humor, murder, stupidity, deception, clever self-preservation — and, of course, sex. Plenty of sex, featuring beautiful young actors and actresses, often with full-monty nudity. This in 1971, an era in which nudity began to assert itself in mainstream cinema, but never this cheerfully and to this extent.

Pasolini would come to regret this parade of flesh. The “Trilogy” inspired a flood of Italian soft-porn knockoffs based on classic works, especially “The Decameron.” There would be several dozen of these imitations, dubbed “Decamerotic” films. Their makers cashed in on the artistic bravery of Pasolini, to his horror.

“I reject my ‘Trilogy of Life,’ ” he wrote in 1975, “although I do not regret having made it.” He explains that for society and its media, “the last bulwark of reality” at the end of the 1960s was “innocent bodies.” Having celebrated those bodies, he later found they had been “violated, manipulated, enslaved by consumerist power.” Sexual liberation had taken a terrible toll on “young people.” The 1975 “Salò”(also a Criterion title) would cover this material, in shocking fashion.

Pasolini’s own sexualty is reflected throughout the trilogy, especially in “The Arabian Nights,” in which homosexuality is presented on even terms with hetrosexuality. The gay Catholic Marxist gave equal time to female nudity, also lovingly shot, but for mainstream audiences the homoerotic tone and images were startling then and would remain so now.

File all that under prelude and hindsight, however. The “Trilogy of Life” films, taken at face value, are grand entertainments, refreshing, funnier than hell and life-affirming.

File all that under prelude and hindsight, however. The “Trilogy of Life” films, taken at face value, are grand entertainments, refreshing, funnier than hell and life-affirming.

“The Decameron” combines cinema and painting, with Pasolini himself at the center as an intense painter charged with painting a fresco. Giovanni Boccaccio’s 14th century work brims with offbeat characters, whom Pasolini presents them in a time-shifting swirl. Some of these short stories are situation comedies, others odd-angle parables.

A worker passes as a deaf mute in order to service a convent full of horny nuns. A killer achieves sainthood by spinning his last confession into a self-serving tale of heroism. An opportunistic young man finds himself plunged into the business end of a shithouse while his intended runs off with his gold. A foolish farmer offers his wife to a doctor in hopes of having her turned into a working horse. She instead is turned into the doctor’s sex toy.

“The Decameron” was shot in the dialect of Naples, at a time when Italian culture was moving in the direction of a monolithic language. As with the rest of the trilogy, much of the acting is done by non-actors.

In “The Canterbury Tales,” Pasolini takes his production to Geoffrey Chaucer’s England, resulting in characters saying things like “Mamma, mia!” Like “The Decameron,” it’s a ragtag collection of stories told by travelers for each other’s amusement. (The two literary works have many parallels.)

Pasolini’s lover Ninetto Davoli, left, takes featured roles in all three films. In “Canterbury” (1972) he plays Perkin, a Chaplin-esque conniver. In real life, Davoli’s decade-long affair with Pasolini was coming to an end, as Davoli fell in love with a woman. The bittersweet sense of loss seeps through the trilogy.

Pasolini’s lover Ninetto Davoli, left, takes featured roles in all three films. In “Canterbury” (1972) he plays Perkin, a Chaplin-esque conniver. In real life, Davoli’s decade-long affair with Pasolini was coming to an end, as Davoli fell in love with a woman. The bittersweet sense of loss seeps through the trilogy.

Sex, money and death play featured roles, again, with a darker tone than in “The Decameron.”

“Chaucer foresees all the victories, all the triumphs of the bourgeoisie, but he also anticipates its inner rot,” says Pasolini, who plays the author as he imagines his tales. Painting was the artform in “Decameron,” here it is the written word.

The devil looms large in two stories. The outlandish final tale features demons torturing damned humans on their way to hell.

“Arabian Nights” (aka “The Flower of the Thousand and One Nights”) is the most linear of the films, framed by an agreeable tale of a clever slave girl and her lover.

Once again, Pasolini mines the sexual content from the ancient literary works, serving his various agendas. Aladdin and his lamp do not make an appearance, nor does the narrator of tradition, Scheherazade, a young woman who tells the tales to her murderous king in a bid to stave off execution.

There is no Islam in Pasolini’s Arabia, a land where the sexes co-mingle with ease. The director presents one sequence in which a trio of youths joyfully agree to an orgy with an older rich man, the homosexuality a non-issue. This is Pasolini’s Arabian fantasia.

The Criterion box set’s visuals (1.85:1) and audio are outstanding, vast improvements on the thin videos circulating since the laserdisc days. Wear remains, but it is rarely distracting. Ennio Morricone’s delicious music is crisp and clear in uncompressed mono.

There are new English translations, glitch-free. Subtitles are easy on the eyes.

A 65-page booklet packaged with the Blu-rays contains a series of fine essays, opening with Pasolini’s watery denunciation of the trilogy.

Pasolini makes several appearances in the Blu-ray bonus features, coming across like an edgy Dick Cavett. Many of his issues are of the place and time — Italy as it left behind Fascism in the early ’70s — with capitalism his primary target. In “Via Pasolini,” the director discusses language, film and modern society. He comes as aloof, combative, odd.

The most sympathetic look at the man comes in a short documentary he made for TV, “Pasolini and the Form of the City.” The director surveys the Italian cities of Orte and Sabaudia, mourning what is lost in the name of progress. It’s a touching piece. “I come from the ruins,” he once said, “searching for brothers who are no longer.”

Criterion continues to offer fine “visual essays” by scholars, this time on “The Decameron” and “Arabian Nights.” There also are examinations of lost and deleted footage from the trilogy’s second and third films. A 2006 documentary looks back at “Pasolini and the Secret Humiliation of Chaucer.”

There are no feature-length commentaries on the Blu-ray set, nor are they needed. Criterion’s coverage of this fascinating trilogy makes for a tale well told.

Check out Glenn Abel on Google+

Leave a Reply